Alcohol - minimising the negative impact of drinking

A young poet asked a famous novelist for guidance: “What is your advice to young writers?" - “Drink, fuck and smoke!” replied Charles Bukowski. Let's put the drinking part of his wisdom to the test!

A recent conversation with a friend brought up the common urban legend: there might be some health benefits related to consuming limited amount of beverages made of fermented grapes (red wines in particular). It is also a well-established fact, that excess alcohol consumption leads to increased risk of developing a number of adverse health conditions ranging from fatty liver disease, through cancers, to heart attacks and strokes.

So is it good or bad?

This type of “duality” of outcome is fairly common when it comes to discussing the health impact of things we eat, drink or do. In fact, it is not impossible for the same thing to have both - a positive and a negative effect - depending on the “dose”.

The U-shaped curves

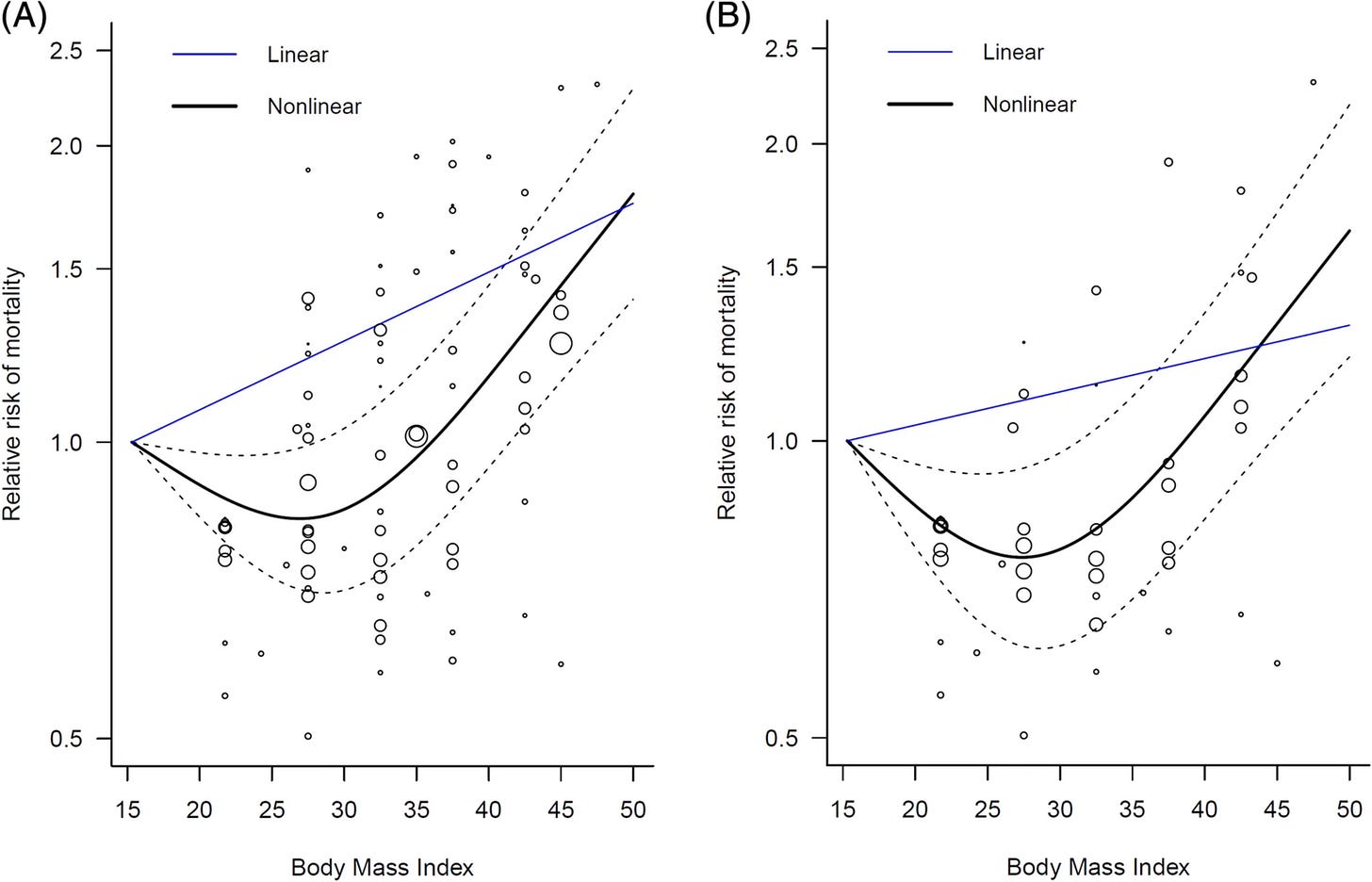

A good example of such relationship can be illustrated by plotting the body mass index (BMI) and COVID-19 mortality. Take a look at the graphs below:

The J-shaped (or U-shaped) curve depicts a situation where too much or too little of something (in this case body weight) has a detrimental impact on survival; the optimum value of the variable lies at the bottom of the curve. Too much, or too little takes you away from optimal outcome.

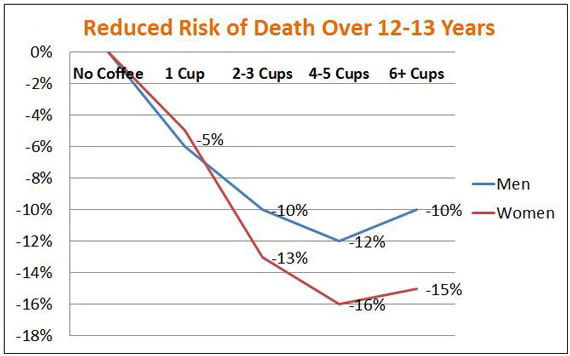

Similar pattern is well documented with relation to coffee consumption:

Every cup of coffee appears to reduce overall risk of death among people who consume it regularly, but after 4 cups a day the trend seems to reverse and the risk starts going up again.

So how much alcohol can I drink to optimise my health?

As I have said before, there are some studies that reported benefits of consuming low amounts of alcohol. In some observational studies, individuals who drink “a little” seem to have characteristics associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk.

Those studies, however, seem to have a significant problem: they fail to account for confounding factors. This simply means that the potential benefit of drinking alcohol can in reality be the result of some other factors. That’s what makes observational studies a really poor tool when it comes to assessing potential benefits of alcohol on health.

You can learn more about why some trials are better for answering certain questions in my post about sugar substitutes; click the link and scroll to “Let’s do Science”.

While some observational studies sometimes try to adjust for some of the confounding factors, no study can ever correct for every possible variable.

What you need to answer is if, and in what amounts, alcohol can help with your cardiovascular health. In theory, the best way to do it is by setting up a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT).

But there is a “but”…

First, those studies would likely need to take decades to complete. Secondly, they would cost a fortune. Thirdly, they would be hard to push through ethical approval (as drinking-related risks are well known). Fourthly (?), nobody would want to be in the placebo arm, and even if they did, it would be impossible to blind it. Fifthly (???), it is hard to define and track how much is considered “low” or “high” consumption. Sixthly, (is that even a word?)… well, never mind.

Luckily there is a tool that can help - a Mendelian randomisation (click link to read how it works).

WTF is Mendelian randomisation? (MR)

MR is a method that scientists use to overcome the bulls**t that can flow from individual observational studies into press articles and into social media feeds. In particular, it can help us deal with the effect of confounding variables without spending billions on an RCT.

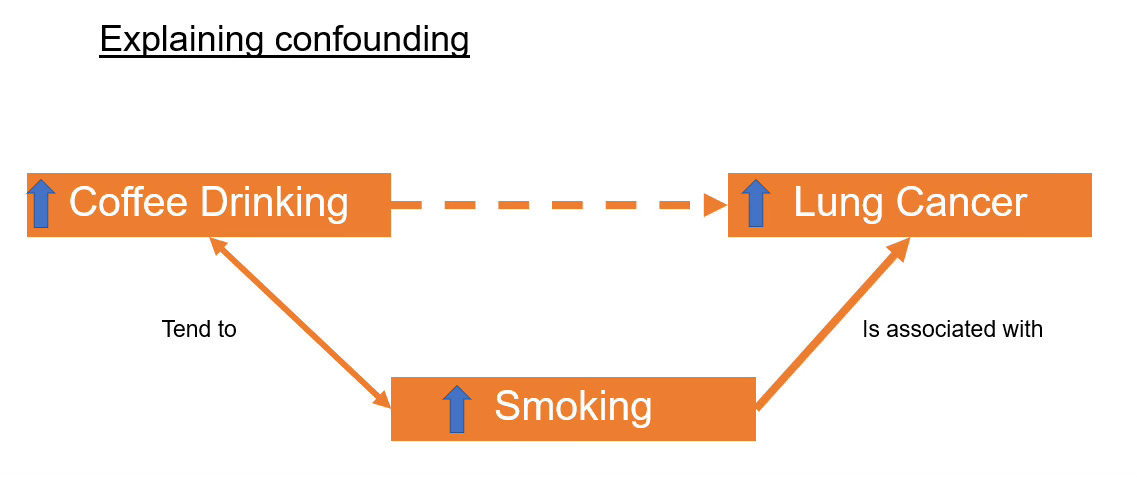

To be sure you are clear on what a “confounder” is, take a closer look at the following example. In the 1970s scientists have observed that drinking coffee may cause lung cancer. Researchers have asked coffee drinkers to indicate how many cups of coffee they drink every day, and found out that those who drink more coffee, are more likely to develop a lung cancer.

What they have forgotten to do, is to check for other factors (confounders) that could attribute to the outcome. It later turned out that most coffee drinkers included in the study were also heavy smokers, and coffee tends to be a drink that goes really well with a fag.

When researchers adjusted for this fact it turned out that coffee does not cause lung cancer at all (source), and may in fact protect from colorectal cancer and lower the risk of diabetes (if consumed outside of Starbucks: without cream, milk, sugary syrups, and served in containers smaller than a bathtub).

Let’s get back to Mendelian randomisation. MR uses gene variants that are linked to a given exposure (in this case, alcohol consumption) as a proxy measure for that exposure. Gene variants are randomly distributed in the population, so using these variants in the place of alcohol consumption essentially constitutes a “natural” randomised trial and eliminates confounding due to other lifestyle or environmental factors.

This may be quite technical, but you can read more here.

But I still don’t know how much can I drink…

Patience….

Biddinger et al. used MR to check if drinking alcohol has any impact on cardiovascular disease risk. The team took data from >350,000 people from the UK Biobank, and followed them up over 10 years period to see how many will develop CVDs (hypertension, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and others).

The genetic proxy used in the MR for this analysis was based on 9 established gene variants associated with alcohol use disorder. Several of these, including variants in ALDH1B and ALDH1C (alcohol dehydrogenase 1B and 1C), directly impact the processing of alcohol and thus affect alcohol consumption by altering the magnitude of adverse side effects, while others, such as variants in DRD2 (dopamine receptor 2), are associated with the behavioural pathways implicated in alcohol addiction.

The authors then used magic statistics to determine if the genetic variants alone were related to development of CVD (even without the use of alcohol), or to confirm that the genetic variants were associated with alcohol-induced CVD by monitoring the levels of gamma-glutamyl transferase, (a biomarker for alcohol use), and by collecting self-reported alcohol intake data. In other words, the authors wanted to ensure that the genetic variants alone are not confounding the impact of the alcohol consumption.

The amount of alcohol consumed was qualified: the authors defined how much is “little” (0-1 drinks per day), “some” (1-2 drinks/day), “too much” (2-3 drinks per day), and “waaaaay too much” (>3 drinks per day) to further remove bias.

Can someone finally tell me how much can I drink, FFS?

Well, turns out not much…

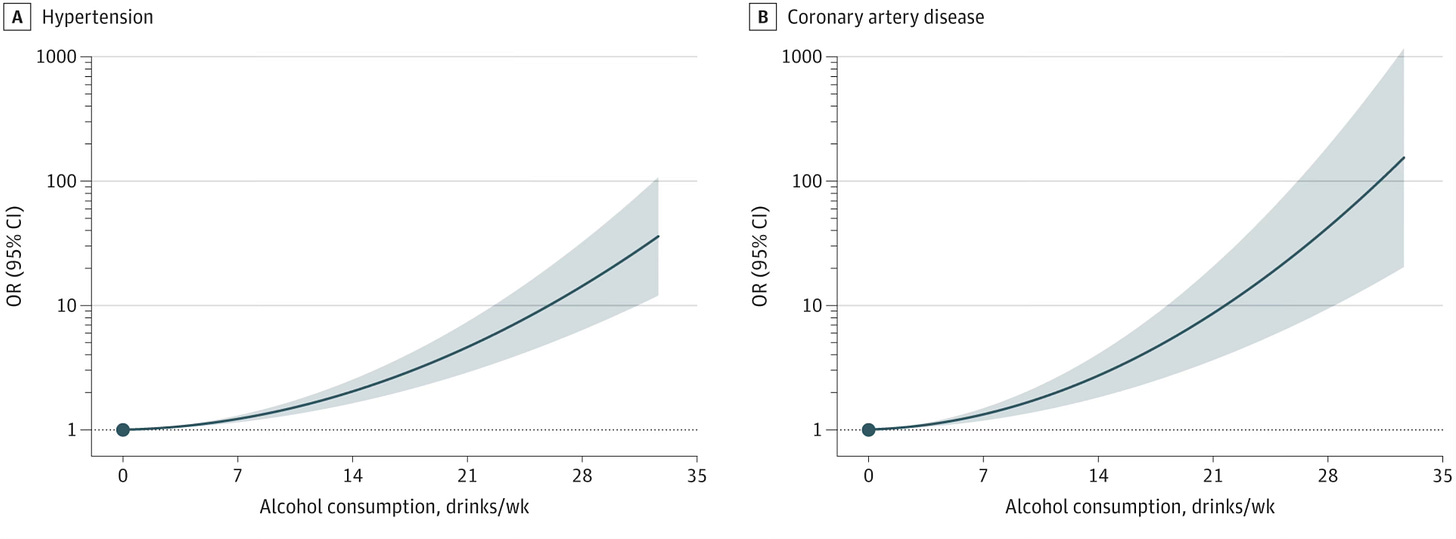

In contrast to the findings of many earlier observational studies, Biddinger et al. found that any level of alcohol exposure is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease. In lay terms - every sip is bad for you, and the more sips you take, the worse it gets.

Each standard deviation increases in genetically predicted alcohol consumption was associated with a 30% higher risk of hypertension (OR=1.3; 95% CI: 1.2-1.4; P<0.001) over the ten-year follow-up, and a 40% higher risk of CAD (OR=1.4; 95% CI: 1.1-1.8; P=0.006). (There was also a clear trend toward increased risk persisted for MI, stroke, and heart failure, but it did not reach statistical significance.)

Even among the light drinking group, every one-drink per day increase in alcohol consumption was found to significantly raise risk of hypertension by 30% (OR=1.3; 95%CI: 1.1-1.5; P=0.003) and CAD by 70% (OR=1.7; 95%CI: 1.2-2.4; P<0.001).

These results seem to refute the theory that low levels of alcohol consumption are beneficial for cardiovascular health and demonstrate that quite the opposite is true – even low intake is detrimental.

Is that it?

No.

The authors also found out that increases in numbers of drinks consumed did not affect the risk equally across drinking groups. Specifically, while every one-drink per day increase in alcohol consumption among light drinkers increased the odds of hypertension and Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) respectively by 30% and 70% as described above, the same incremental increase in genetically predicted consumption raises the odds of hypertension and CAD in moderate drinkers by 70% and 80%, respectively. In the heavy drinking group (>3 drinks/day, or >24.5/week), a one-drink daily elevated hypertension risk by 160% (this is not a typo) (OR=2.6; 95% CI: 1.6-4.2; P<0.001) and CAD risk by a whopping 470% (and neither is this) (OR=5.7; 95% CI: 2.4-13.5; P<0.001).

The continuous representation of this relationship is shown below: CVD risk increases exponentially with progressive levels of alcohol consumption.

In simple terms, even one drink increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, and every other drink not only adds, but in fact multiples the negative impact that alcohol has on your cardiovascular health.

Alcohol and diseases impacting longevity

You have already learned that alcohol consumption has a devastating effect on the cardiovascular health. This is not the only system affected by consumption of alcoholic beverages. Here are the other well documented impact of alcohol on the body:

Alcohol and cancer

Alcohol is a group 1 carcinogen, classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). This means it is definitively linked to an increased risk of several cancers.

Group 1 carcinogens, apart from alcohol and its metabolites, include tobacco smoke, asbestos, arsenic, plutonium, ionising radiation, certain pesticides, UV exposure, or engine exhaust fumes. All Group 1 carcinogens are characterised by proved risk of developing cancers, and the lack of minimum safe dose (even the smallest amounts increase the risk of cancer).

Alcohol consumption alone is directly linked to over 750,000 cancers diagnosed each year (worldwide). The 5 most common alcohol-related cancers include: breast cancer, colorectal cancer, oesophageal cancer, liver cancer and mouth and throat cancers.

The risk is well quantified and significant. For example, in women without the genetic predisposition (like BRCA1 and BRCA2) alcohol is the most significant risk factor for development of breast cancer. It is also modifiable. Ethanol increases levels of oestrogen and other hormones associated with hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer.

The metabolite of ethanol, acetaldehyde, is another carcinogen further increasing the risk. The risk of breast cancer alone increases by ~7–10% for every 10g (0.3 oz!) of alcohol consumed daily.

Alcohol and liver diseases

Alcohol directly damages liver cells. So do the metabolites, leading to progressive liver conditions:

Fatty Liver Disease: Excess fat accumulates in liver cells due to alcohol metabolism leading to liver damage.

Alcoholic Hepatitis: Inflammation and damage to liver tissue caused by prolonged alcohol use.

Cirrhosis: Irreversible scarring and loss of liver function due to chronic alcohol consumption.

Liver Cancer: Increased risk due to cirrhosis and chronic liver damage.

Alcohol and mental health

Alcohol is a neurotoxin (potent toxin of your nervous system) and significantly disrupts brain function and emotional regulation:

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD): Chronic dependence on alcohol, characterised by physical and psychological symptoms.

Alcohol-Related Dementia: Long-term alcohol use impairs cognitive function and memory.

Peripheral Neuropathy: Nerve damage leading to pain, tingling, or numbness, especially in the extremities.

Mental Health Disorders: Alcohol is linked to depression, anxiety, and suicide risk.

Sleep disturbances and conditions related to the lack of regenerative sleep.

The damage done by alcohol to the nervous system might not be recoverable, especially if it impacts the brain during its development (from birth to approximately 25 years of age).

Alcohol and gastrointestinal diseases

The digestive tract and associated organs are highly susceptible, as they are directly damaged as the alcohol passes thought the digestive tract. Most common problems include, but are not limited to: Gastritis, Pancreatitis and Oesophageal and Stomach Cancers.

Alcohol and the risk of accidents

Alcohol is one of the most significant factors contributing to personal injuries (falls, fights, etc), workplace injuries, road traffic accidents, unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases. All of the above have significant impacts on you being able to live a long and healthy life.

Alcohol and immune system impairment

Chronic alcohol consumption weakens immune function, leading to: Increased Infection Risk (higher susceptibility to pneumonia, tuberculosis, and other infections) as well as Slower Wound Healing (impaired immune responses hinder recovery from injuries or surgeries).

Alcohol and reproductive health issues

Alcohol impacts fertility and pregnancy outcomes. Most common conditions include Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD), Impotence and Infertility. Alcohol further disrupts hormone balance and reproductive function in women.

Alcohol and bone health

Alcohol interferes with calcium absorption and damages bone health, leading directly to Osteoporosis (reduced bone density) due to alcohol's impact on calcium metabolism and general myopathy (muscle weakness caused by alcohol's toxic effects). The impact of those changes becomes more significant as we age.

To sum it all up: there is no safe dose of alcohol, every drink has a negative impact on your longevity, toxicity increases with each dose consumed, some damage may be permanent. At Solutions Makers, we strongly recommend elimination of consumption of alcohol, or a significant reduction of the consumed volume to no more than 1 unit per day, but on no more than 2 days per week (women) or 3 days per week (men).

So what now?

It seems that no level of alcohol intake – however small – is beneficial for cardiovascular health, or any other aspect of your health.

Even those of us who consume alcohol at low levels have elevated CVD risk relative to abstainers. The initial increase in risk (small glass of red wine a day) is relatively small. Perhaps even small enough to be mitigated by potential benefits (like social interactions) that often coincide with consuming alcohol.

Each subsequent drink however greatly increases odds of dying from a heart disease. And this risk analysis does not even take into account the other (non-cardiovascular) unwanted outcomes related to alcohol consumption: such as liver disease, or cancers.

It also means that if you drink more than you should (and you should not be drinking at all!), every drink you don’t consume dramatically reduces the risks to your health. This means that meaningful reduction in health risks does not require the complete abstinence from alcohol. For those who drink heavily, every reduction in intake can have enormous effects in lessening the risk to your health. For example, a person who drinks three glasses of wine per day can reduce their CAD risk by over 60% just by shifting to two glasses per day - which is a significant and totally achievable improvement.

Anything else?

Yes. Charles Bukowski was wrong.

Well, at least when it comes to drinking and smoking.