Exercise for health - Part II

Peak aerobic capacity consistently proves to have a profound impact on all-cause mortality. Here is how to improve your health, and enjoy the longevity you are working to build.

There aren’t that many reliable predictors of morbidity and mortality. Doctors know that any amount of alcohol consumption increases all-cause mortality. So does tobacco smoking, exposure to radiation or other environmental toxins.

When it comes to longevity, the most significant predictor associated with reduction of all-cause mortality at any age is peak aerobic performance, also known as VO2max.

WTF is VO2 max?

When engaging in any aerobic activity (such as walking, hiking, or running or swimming) your muscles need a steady supply (volume, as in V) of oxygen (O2) to produce the forces required for repetitive movements. This oxygen usage is measured as VO2max, expressed in litres per minute (L/min) or, when adjusted for body weight, in millilitres per kilogram per minute (ml/kg/min).

The maximum amount of oxygen your body can utilise during intense exercise is called VO2max, which serves as a key indicator of aerobic performance and overall cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF).

VO2max is closely tied to the body's capacity to deliver oxygen to the muscles. This in turn depends on your cardiac output. Cardiac output is influenced by maximum heart rate (HR), which naturally decreases with age. As a result, the highest possible VO2max also declines as you get older.

While this age-related decline means that your ability to briskly walk uphill in your 70s or 80s isn't what it was in your 30s or 40s, a certain level of aerobic capacity remains essential for performing everyday tasks—whether it’s climbing stairs or carrying groceries.

How is VO2 max measured?

The most precise way to measure VO2max is through a specialised lab-based exercise test. In this controlled environment, the individual wears a heart rate monitor and a snug mask that tracks oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production while s/he performs increasingly intense exercise, typically on an inclined treadmill or stationary bike, until s/he reaches their limit.

Lab testing is not always convenient or accessible. Fortunately, there are several at-home methods that, while less precise, can still give you a good estimate of your VO2max.

One of the more accurate tests involves gradually increasing power output on a stationary bike, with each level maintained for 2.5 minutes. In this scenario, your VO2max is inferred from your peak power output.1

Other methods include timed runs, such as a 12-minute run or a 1-mile (1.6 km) walk2 3, which is the sub-maximal version of the test4.

There are also various online calculators that can help you determine your estimated VO2max based on these tests, comparing your results to others of the same age and sex. These at-home tests all rely on equations that convert your performance metrics into an estimated VO2max, offering a practical way to gauge your aerobic fitness without the need for specialised equipment.

At home testing is quite challenging though. It can be tricky to judge the right intensity the first time you estimate your VO2max. For instance, during your first 12-minute run, you might start too fast and burn out before the end, or you might begin too slowly, not pushing yourself to a true maximal effort. While it’s not always enjoyable to do these maximal effort tests, repeating the test on different days is the best way to get a more accurate assessment. With each attempt, your results are likely to become more consistent as you fine-tune your pacing and effort.

What should I aim for?

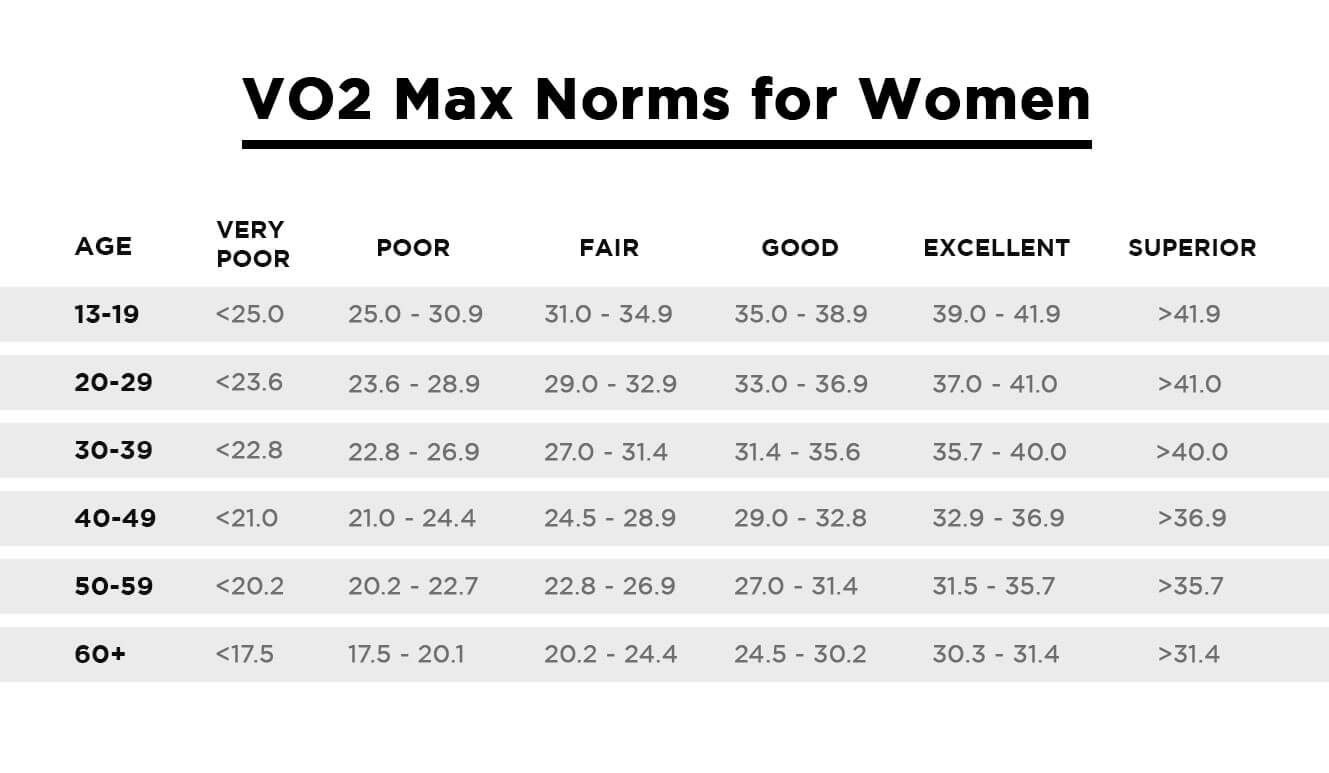

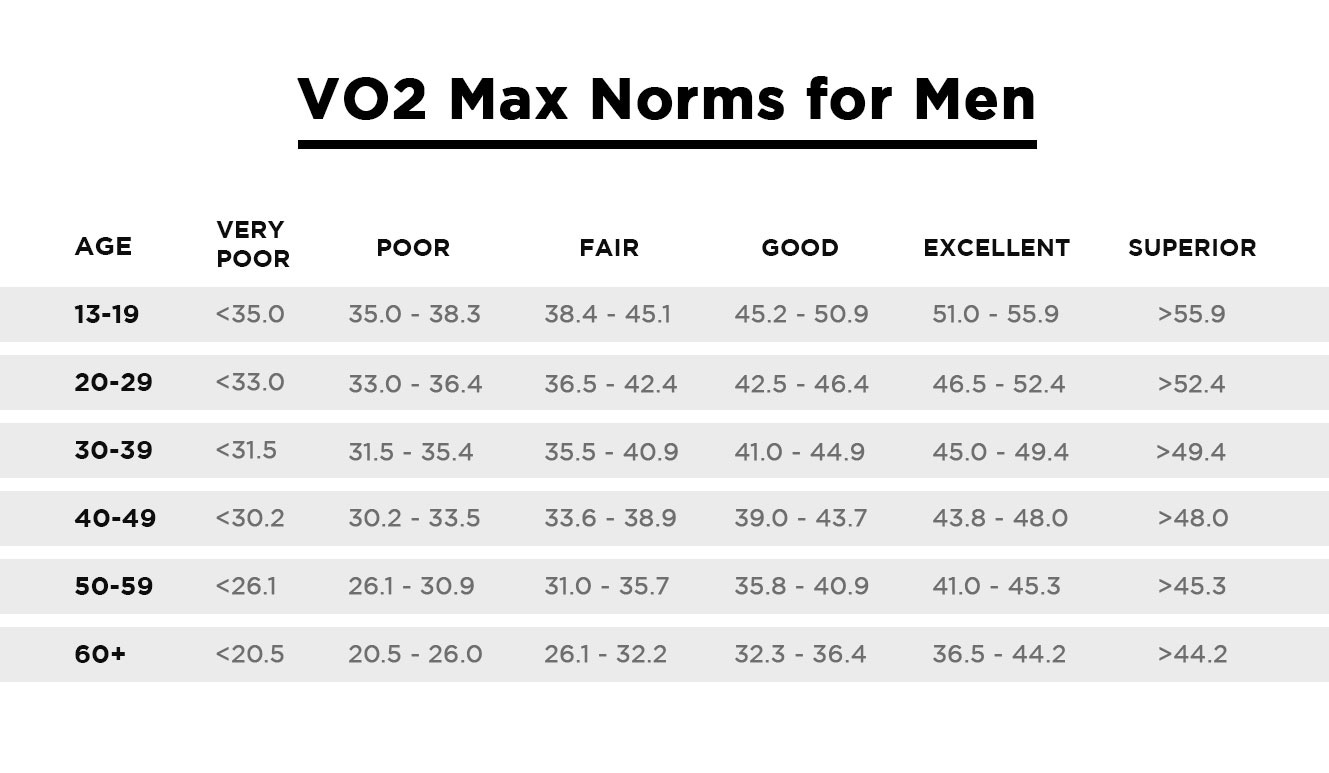

As a rule - the higher the better. The tables below show optimal values (per age) for women and men:

To optimise longevity, the most practical purpose, aim for the “superior” level of the previous (“younger”) age band. For example, a 45 year old male should aim for VO2max above 49.4, while a 34 year old woman should aim for VO2max >41.

And yes, if you have noticed that a 60+ year old “superiorly trained” male has a higher peak cardiovascular output than a 20-year-old female trained to the same level - this is not a mistake; this is the reality of biological differences between males and females.

Individuals with a high VO2max are indeed likely to have lower amounts of excess fat mass, but either fat mass or percent body fat is generally not a strong predictor of maximal oxygen consumption5.

This means that if two people have the same total weight, the one with more muscles and less fat will have a higher absolute VO2max, as well as a higher VO2max normalised by body weight (ml/kg/min).

Why higher VO2max may help me live longer?

For decades, research has shown that high cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), as measured by maximal exercise testing, is a strong predictor of both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.

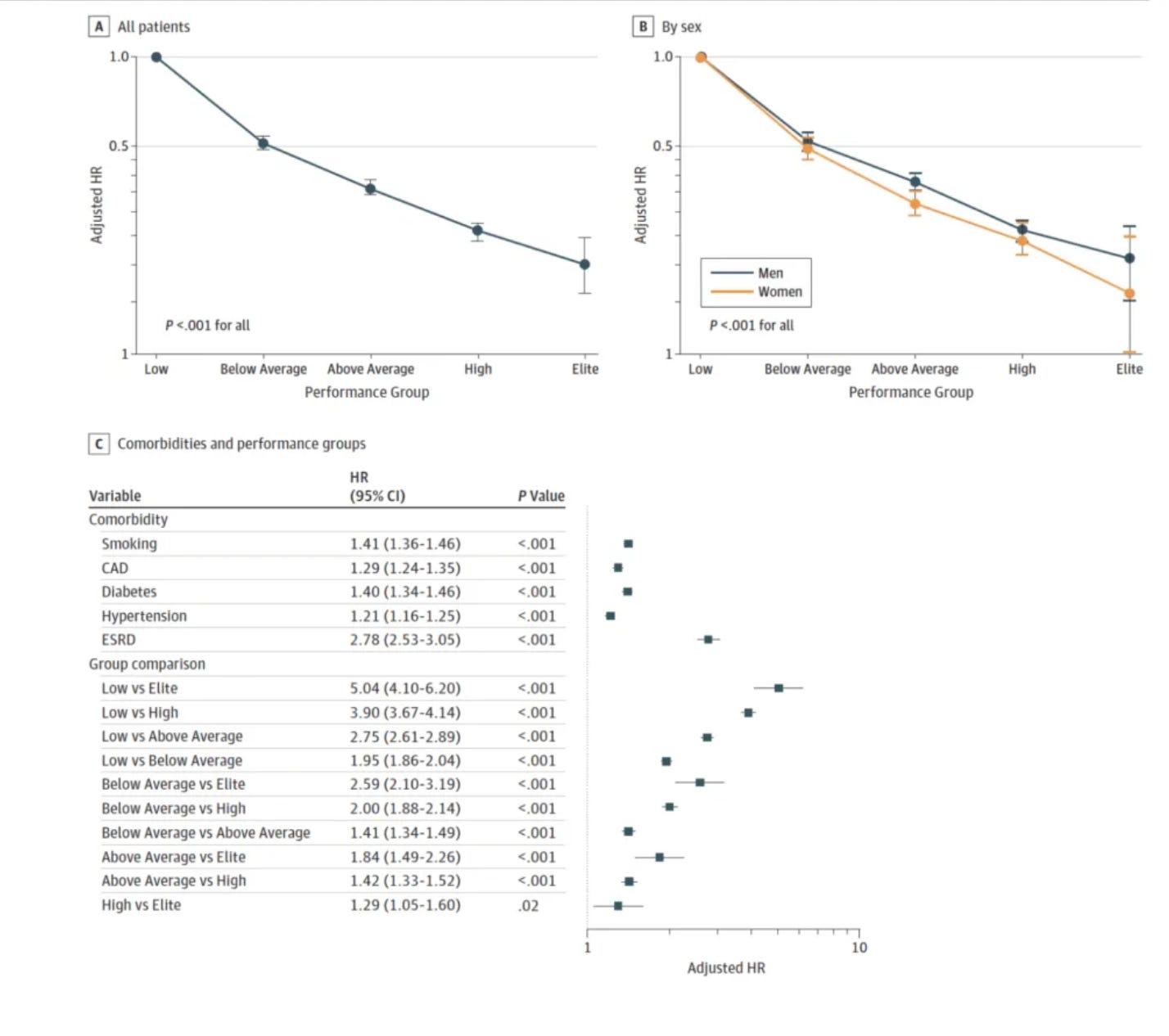

In 2018, Mandsager and colleagues published a retrospective study of more than 120,000 adults undergoing treadmill exercise testing, a common method for measuring VO2max.6 After a follow-up of over 8 years, the authors showed that those who had high VO2max (for their age and sex) had the lowest risk of both cardiorespiratory and all-cause mortality.

When compared to individuals in the elite category, the lowest 25% of cardiorespiratory fitness (the “low” group) had more than a five-fold increase in risk of all-cause mortality!

This means that someone in the lowest category of fitness was five times more likely to die of any cause than someone with high VO2max for their age. Some of the change in mortality risk can be attributed to a decreasing prevalence of comorbidities (i.e., hypertension, diabetes) with increasing cardiovascular fitness.

To appreciate the astounding magnitude of this association between low VO2max and mortality risk, we need only look at how it compares with other predictors of all cause mortality.

It seems that being unfit has a much greater influence on lifespan than conditions like hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, or even smoking.

Important stats from the study

Going from being low to being below average is a 50% reduction in mortality over a decade.

If you then go from low to above average, it’s about a 60% or 70% reduction in mortality

The lowest improvement is going from high to elite

Here’s what’s interesting…

If you compare someone of low fitness to elite, it is a five-fold (500%) difference in mortality over a decade

To put this in the context of what we know is bad for our health:

Smoking - 41% increase in mortality over the decade

Coronary artery disease - 29% increase in mortality over the same time

Diabetes - 40% increase

High blood pressure - 21% increase

End-stage renal disease, about 180% increase in mortality

This is the same difference as between low and above average cardiorespiratory fitness!

Pause and reflect on how much improvement in mortality comes from improving your fitness

Oh fuck… that’s significant…

Quite significant.

The results above are replicable. Kokkinos followed over 750,000 subjects for over 10 years and noticed that across all age group (up to the age of 95) that people with VO2max in the bottom 20% (for their sex and age) had more than four times (4x) increase in the risk of all cause mortality than those in the top range of VO2max7.

Kokkinos et al. also found that comorbidities – including smoking, diabetes, and cancer – all increased the risk of all cause mortality less than being unfit. Even age was a worse predictor of mortality than VO2max.

Let that sink in: having poor cardiovascular fitness is more strongly associated with the risk of death than being old. And in contrast to the inevitability of advancing age, you actually have a degree of control over your fitness through specific types of exercise8.

VO2 max is a very robust predictor of all-cause mortality because it provides an integrated metric for overall metabolic fitness and high-intensity aerobic exercise over a long period of time, and takes your body weight into account9.

In short, if you want to live longer, consistently engaging in specific types of aerobic exercise (like Zone 2 training) is key.

Why being fit helps you live longer?

Interestingly the influence of VO2max on mortality risk goes beyond cardiovascular health.

Regular exercise training for increasing VO2max results in physiological adaptations that increase your capacity to use oxygen to break down and use fuel for energy in a state of distress. Although VO2max is measured during an exercise test, the physiologic distress of illness also requires a significant amount of energy to mount an immune response and recover.

The higher your VO2max, the more reserve or excess energy you have and the smaller percentage of your capacity that has to be used for the process of fighting off pathogens or mounting an inflammatory response.

This seems to be an important contributor to the decreased mortality because those with the highest VO2max have a much higher likelihood of tolerating cancer treatments, surviving seasonal viruses or respiratory illnesses, or being better candidates for life-extending surgeries.

How to improve my VO2 max?

The only way to achieve a higher VO2max is to be aerobically active for many years, which gradually results in denser levels of mitochondria in skeletal muscle (Zone 2 training!), which in turn allows the muscle to use a greater volume of oxygen to convert into energy.

Achieving meaningful changes in mitochondrial function or density requires consistent, long-term training (life-long). A few weeks or even months of exercise won’t be enough to significantly alter these cellular adaptations. Likewise, VO2max is heavily influenced by shifts in body composition, which, like cellular changes, occur gradually. Since exercise profoundly impacts skeletal muscle, it's no surprise that fat-free mass plays a crucial role in determining VO2max.

So, in addition to redefining your weekly exercise routines to include targeted aerobic, optimising nutrition will help to improve your VO2max (coming soon!).

So how fast can I improve?

When you start today, you are already making an improvement. But - you should aim for life-long training (ideally designed by your longevity advisor). You will not be able to see the results in your VO2max test in a few days. However, you might be able to see noticeable improvements in as little as few months.

One study in untrained people has shown that only 12 weeks of stationary (indoor) cycling at 70% of VO2max for 45 minutes three times per week can increase VO2max by 18-30%10.

Regardless, none of these changes are happening in a week or even two, and you’re certainly not getting from the lowest to the highest level of fitness without dedicating significant time (years) and effort (2-3 times per week).

What are practical goals and plans I can make?

The maximum achievable VO2max for any given person declines with age. It can not be stopped, or reversed. Your physical decline which starts in the early 20s can be only slowed down through your healthy choices.

According to P. Attia (2021), our ability to continue performing the basic activities of daily life into old age (examples shown in Figures 3a and 3b for men and women respectively) depends on maintaining a significantly above-average VO2max throughout our lifetimes11.

When first starting to exercise (or returning to exercise after a long period away from training), any cardiovascular exercise will start to raise VO2 max.

This means that for untrained people it is best to start out with Zone 2 workouts (or even Zone 1, if they are really unfit). This helps build consistency and increases exercise tolerance before jumping into higher-intensity training.

After having 6-9 months of Zone 2 training under your belt, you should aim to start adding in one day of VO2max training to keep improving your VO2max.

What training should I add to my Zone 2 plan?

It has been repeatedly shown that the best way to increase your VO2max is with high-intensity interval training (although not necessarily what is called a “HIIT” class at your local gym).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Solutions Manual to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.