Mental Edge

How to maximise your mental and cognitive processing power - a useful guide for all people who rely on thinking, analysing and creativity in their everyday life.

The internet is full of “advice” on how to maximise muscle growth, strength or physical performance. I am sure this is important for those who do manual labour or frequently need to perform physically demandimg tasks.

In my daily work, I rarely need to sprint, jump, kick or run. Instead, I rely on my ability to think clearly, make important decisions (often without sufficient information available), complete large volumes of intellectual work in short amount of time, design, plan and review documents, come up with creative problem-solving ideas, etc. All of those tasks need to be completed with maximum accuracy, and at the right time. For this reason, I find it valuable to maximise my cognitive performance.

Why?

Finishing all tasks in 6 rather than 10 hours makes a big difference to my personal and family life.

Better decision-making means more gets done, and there are less mistakes to fix later.

Well-designed study protocols mean higher quality evidence, and improved patient safety.

More accurate reviews translate to faster and better outcomes every day.

Better analysis (of data, situations, or evidence) equals more precise action plans.

10% better decisions than those your competition makes accumulate over time, giving a dramatic advantage to your business, career or well-being.

Here is how to dramatically increase and sustain your mental edge, laid out in 10 simple, powerful, evidence-based tactics. Many of those methods are used by artists, researchers, Nobel-prize laureates, clandestine intelligence operatives, surgeons, heads of state, business leaders, and other people who want to maximise their cognitive performance, sustain mental energy, and stay ahead of the crowd (in business and personal life).

Today you will learn how to maximise and enhance your mental capabilities, dramatically increase resilience, improve decision-making, reduce anxiety, free up time for family, friends or hobbies, fall asleep in less than 3 minutes from closing your eyes, any many more.

Reference section and links throughout the article will provide you additional context, more information, extra details, or even education materials and videos.

Enjoy!

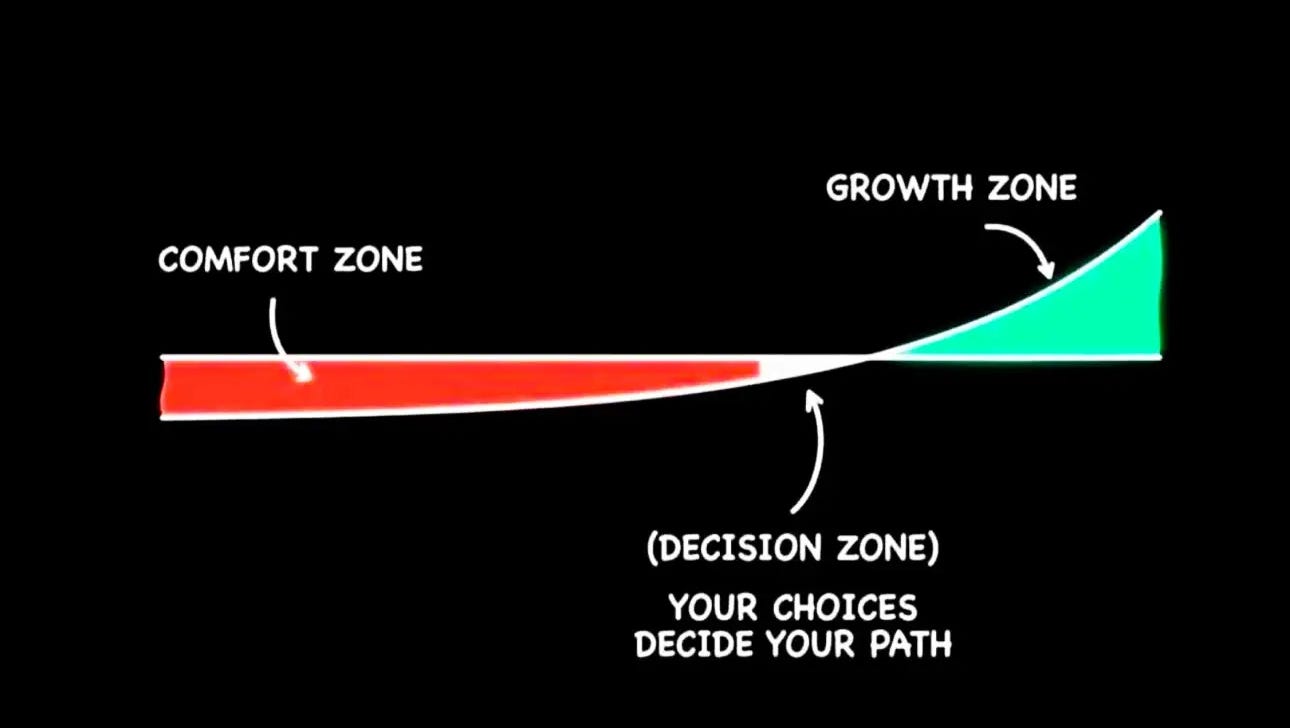

Stay outside of your comfort zone as often and as long as you possibly can

Look around. If you see people who are “triggered”, annoyed, anxious or unable to handle uncomfortable situation - smile! Not only this is fun to watch, it also means you are likely to have a significant advantage over them, provided you can learn to manage and handle discomfort.

Lack of comfort is an excellent indicator of your brain being stimulated. You want as much of this as possible.

The easiest way to put yourself outside of your comfort zone and to stimulate your brain is to learn something new1. Anything. While not all learning is equally challenging, even memorising poems or learning pieces of text by heart are powerful cognitive performance tools2.

Ideally, try to ALWAYS be in the state of learning: driving, swimming, skiing, languages, new concepts or theories, technical skills, DIY, playing instruments, sailing, political views, cooking, art forms, religious perspectives, exercise techniques, learning from books, collecting stamps, programming, philosophy, archery - doesn't matter. Learn!

The worse you are at something, the more benefits you will get from learning. Whatever you choose to learn, don’t expect to become really good at it - prioritise new things and new learnings over repeated practice or improvement of already acquired skills3.

You may suck at playing piano, or struggle to write even the simplest piece of computer code - that is OK (unless you need those skills, of course, for any reason). What matters, is that you are learning something new.

Nothing degrades your brain more than staying in your comfort zone. Challenge yourself and the people you care about4. This will give you an incredible mental advantage over growing numbers of overly comfortable, mentally stuck crowds.

Learning is also fun.

The drawback - it might be costly and time consuming (but so is a gym membership).

Learn to wake up without an alarm clock

The vast majority of “sleeping advice” is marketing garbage. You don’t need better alarm, smart sleep analysers, cooled blankets, new pillows, improved springs or foam in your mattress, daily routine, fixed temperature or humidity… This is all bulls*it.

It does not matter who you follow on social media, or how many hours your phone (or watch) suggests you should sleep for. There is no “optimal sleep pattern”, or the “right time to go to bed”. There is no best time to wake-up at. This all depends on your body’s internal clock, which regulates your sleep/wake cycle.

Take a look at this:

70% of people in Western Countries admit that they suffer from insufficient sleep (National Sleep Foundation, "Sleep in America Poll")

By the end of primary education more than half of Americans experience sleep deprivation (American Academy of Pediatrics, "School Start Times for Adolescents", pediatrics.aappublications.org).

By the end of high school, the percentage rises to >70% (Reference: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System", cdc.gov).

The primary causes of sleep deprivation stem from a significant mismatch between our body's evolving biological requirements for sleep and the relentless pace of our daily lives

- Harvard Medical School in their "Sleep and Health"

This discord forces individuals to often adjust their innate sleep patterns to conform to schedules imposed by mechanical timekeepers, sidelining the natural cues from their circadian rhythms.

Matthew Walker's "Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams" suggests an effective strategy for enhancing mental acuity: it proposes letting the body's own rhythms dictate the start of the day, rather than being woken up by an alarm.

Apart from reduced anxiety, improved mental clarity, sustained performance, and improved mood, learning to wake up without an alarm allows you to avoid other dangers of ”closing your eyes for just 2 more minutes”:

Last time I hit the “snooze” button after the alarm went off, I woke up 15 years later, married, with three kids, and a dog…

- M. D. Zatonski

You can control when you go to sleep, which will later precisely guide your waking-up time. While first few days are hard, most people can learn to live and wake up without an alarm clock in approximately 2-3 weeks.

To reset your brain’s wiring and gain an incredible mental edge over most people you will ever meet, simply let your body decide how much sleep it needs.

It is also O.K to take naps during the day if you need - good nap only takes 10-15 minutes, and can be done during breaks in most work settings.

Further down, I will teach you how surgeons, soldiers and other high-performing people can learn to fall asleep in any position and in any environment in less than 3 minutes!

Drink 500ml of water within 5 minutes from waking up

This is literally it.

Just try it once. In just 10 minutes after completing your “forced” hydration, you'll likely notice a significant increase in alertness, awareness, and mental activation, surpassing any previous state before adopting this simple practice.

Believe it or not - this effect is rooted in basic biological principles567, and gives you a strategic edge over the countless individuals who start their day under-rested, dehydrated, caffeinated and anxious from reading social media feeds first thing in the morning. It hardly takes any time and can be practices anytime and everywhere.

Spend few minutes each morning in a place with minimum sensory inputs

You might be surprised to learn that this practice is recommended by meditation experts, religious leaders, and military intelligence operatives alike. It is rooted in the fact that your brain can either take information in (absorbing mode) or process already acquired information (indexing mode), but it can’t do both at the same time (dual-process theory).

In order to “push” your brain into indexing mode you need to minimise sensory input. We have 5 primary senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch) that trigger your brain’s default absorbing mode, automatically limiting creativity, problem-solving, and other cognitive skills - often for the rest of your day8.

All you need to do is

to avoid as much of the sensory inputs at the first 10-15 minutes of your day as you can. This includes bright lights/screens (sight), music, TV or noise (hearing), strong flavours and smells, including foods and strong drinks - like tea or coffee (smell and taste), and ensure relative personal and thermal comfort (touch).

Furthermore, it's important to note that cortisol (“stress hormone”), naturally peaks in the first hour after waking. This elevation in cortisol, combined with sensory input, can lead to feelings of anxiety, frustration, and irritation early in the day. If you've ever felt your mood sour before even reaching work, this hormonal interplay explains it.

Find a comfortable place with neutral smells, low light and low noise levels, no screens and give your brain time to index itself. People with various backgrounds call this prayer, reflection, meditation, mindfulness, or something similar. Biologically, all you need is some time for indexing9 - no need to give this simple practice any fancy names or theories.

By dedicating at least 15 minutes each morning to let your brain index and orient itself following sleep, you unlock cognitive resources essential for excelling throughout the day. This quiet time fundamentally enables mental indexing; benefits of this practice accumulate over time.

Eat small meals every 2-3 hours

Hunger kills your brain’s cognitive powers (as it prioritises search and consumption of food)10. It seems (and it is) quite obvious and well researched11.

Yet, surprisingly, one in three professionals routinely skip lunch, and >50% allot less than 30 minutes for their mid-day meal, often choosing quick, packaged snacks over a well-rounded meals.

For unknown reasons (and against all evidence) >67% of millennials are under the false belief that skipping lunch is a productive strategy for their career advancement.

Large meals have a similarly devastating impact on cognitive performance, as your body will switch to prioritising food absorption and fat storage (if the meal had more than 400-600 kcal, depending on your activity levels immediately after eating).

To maximise brain power (at work, at school, during exams, etc) aim to eat small meals every 2-3 hours, ideally composed of unprocessed foods (vegetables, fruit, cooked lean meat and fish, whole grains, diary, nuts, seeds, other fermented foods).

Such routine will not only help with your thinking, but also dramatically improve your sleep and physical performance. It will also allow you to go into prolonged fasting if required (for example when travelling, or during unforeseen circumstances), without significant disruption to your life, provided that you remain adequately hydrated.

Avoid (or break) routines

If you mainly absorb information pushed by “self-help” gurus and social media “experts” you might falsely believe that you a need to create and stick to a “routine” to be happy, fulfilled, skinny, successful and rich.

Exercise routine, morning routine, work routine, family routine, holiday routine, rest routine, wind-down routine, bed-time routine, surveillance detection routine (SDR), bathroom routine - endless bullsh*it. Not only trying to achieve any of those things may be impossible for you, it will also make you feel bad if you slip or are unable to maintain them.

Furthermore, the evidence shows clearly that routines are NOT good for your brain, cognitive performance and overall wellbeing. This includes the “routine” described in this article.

Be very flexible with all the routines you might have. The more discomfort, the better. Repetition of any learned process, although easy and automatic, does not engage your brain.

What is interesting, is that even those who try to push or sell routines, books about routines, or apps to create routines sometimes notice themselves how counterproductive their advice is. Many of the “influencers”, without seeing the contradiction in their sales routines, actually recommend not to follow their own advice. Yes, you have read this correctly: even those who convince you to establish routines, encourage you to break them…

Routines tend to become less effective over time. Your body and mind adapt quickly to the new “reality”. This is why even physical performance coaches encourage people to change their routine (after convincing people to establish them first).

Similar principles apply to maximising your brain power and mental advantage.

Aim to intentionally break your routines: skip a meal, change the time you go to bed, change the foods you eat, change meal times, adjust your exercise routine, take a different road to work, etc).

An additional benefit of intentional breaking of established routines is increased mental flexibility and adaptability to new or changing environments, which has a dramatically powerful and positive impact on your resilience.

Do some exercise (unfortunately…)

Despite my contempt for physical exercise, all the evidence clearly points out that exercise is required for optimal brain function.

Luckily, this does not mean that you have to spend time at a gym. You don’t need a coach. You can ignore “influencers”. You also don’t need to create or stick to a “workout routine” (see above).

There are however some rules to maximise the impact from physical exercise:

Aim to exercise in the afternoon (not in the morning, not in the evening)

Aim for Zone 2 effort12. Zone 2 cardio workouts can be any modality of aerobic exercise that keeps your heart rate in the 60-70% of your maximal heart rate (HRmax). Here is how to estimated your HRmax:

Haskell & Fox formula - the most common:

HRmax = 220 − ageInbar formula:

HRmax = 205.8 − (0.685 × age)Nes formula:

HRmax = 211 − (0.64 × age)Oakland nonlinear formula:

HRmax = 192 − (0.007 × age²)Tanaka, Monahan, & Seals formula:

HRmax = 208 − (0.7 × age)

Repetitive (“rhythmic”) exercises13, such as walking, running14, swimming, biking, rowing, etc seems to have an edge over more complex tasks (as yoga, martial arts, team sports, skiing, horse riding, etc) when it comes to brain performance15, as the repetitive movements and minimally engagement of cognitive power can seem to help with indexing of information after first 10-12 minutes of working out16.

You don’t need to exhaust yourself. In fact, even walking is sufficient to maximise the cognitive function. Walking can be combined with carrying heavy weights on your back (rucking; or “loaded march”) for additional strength and endurance benefits.

Digital detox

I have already touched upon this topic here. I was surprised to learn that there any many people who do not understand how big of a threat to their mental capability is sucked out by using mobile devices. And the highest risk of running your mental advantage happens when you use screens in the evening.

Let’s be honest - in today's era, escaping the digital realm is virtually impossible. Mobile devices, laptops, tablets, computers, and an array of other digital tools saturate our lives, claiming to enhance work efficiency, foster connections with loved ones, and simplify daily chores.

Some of those claims might be true, but…

There is nothing that leeches your mental energy more than a smartphone or a tablet. Each application on your smartphone is designed to hijack your attention. The relentless influx of notifications, messages, and updates rapidly saps your cognitive energy, depriving your brain of it’s capacity to process and organise information.

Although sustaining high mental engagement might be feasible in the afternoon, extending this digital engagement into the evening jeopardises your sleep quality17 (including ability to fall asleep), mental recuperation, and your capacity to function optimally the following day18.

To mitigate these adverse effects, it's imperative to:

Turn off all notifications on your phone, and only switch back on notifications for incoming calls and messages from people in your address book.

Switch your mobile device to silent mode and stash it out of view (for use in emergency only) as the sun begins to set, but no later than 3-4 hours before your planned sleeping time19.

Beyond the well-documented detrimental impacts of light exposure from screens, the more dangerous threat lies in the psychological compulsion to check your device. This continuous stream of interruptions forces your brain to remain in a perpetual state of information absorption, preventing the desired process of indexing.

Delaying this process, especially in the lead-up to sleep, can indeed interfere with the ability to relax and transition into sleep effectively20. This notion aligns with research on how cognitive arousal before bed, resulting from engaging activities or exposure to stimulating content, can disrupt sleep onset and quality, as well as significantly impair cognitive performance in the long-term21. Prolonged disruption of normal REM sleep will further lead to more unpredictable sleep cycle and decreased brain performance.

Learn to fall asleep quickly (and consistently)

Most people without underlying medical conditions and without substance abuse, can learn to fall asleep rapidly (within 120-180 seconds from closing their eyes) with only 2-4 weeks of training.

Believe it or not, falling asleep quickly is a learned skill. It is also an essential skill in maximising your mental advantage. It will help with other methods and skills described above (such as waking up without an alarm, or taking powerful naps).

You might already follow a bed-time routine: perhaps a shower, brushing your teeth, perhaps winding down with a book. While these activities are beneficial in their own right, they might not contribute significantly to enhancing your mental acuity. They are also not helpful when your routine is changes, you are travelling or you need to fall asleep (a short nap) at work - after all it might be impossible to shower and read for an hour before taking a 10 minute Power Nap.

Instead, spend the next 2-3 week on establishing a new skill - learn to rapidly fall asleep on demand, in any conditions, in any position. There are two methods:

Learn to fall asleep by replacing your usual bed-time routine

Dedicate 10-15 minutes after your usual pre-sleep activities to allow your brain to quietly process and organise the day's events (indexing). Reflect on the personal connections you've nurtured, pay attention to how your body responded to the meals you have eaten during the day, consider anything you might be grateful for, etc. Make you brain to think about pre-determined things, activities and reflections, and don’t allow your thoughts to run wild. Gently stay in control of the process.

The aim of this simple ritual is to ensure your mind efficiently processes any residual information, facilitating a state of mental clarity and a positive disposition as you drift off to sleep. Within few weeks it will be the only activity you will need to do in order to quickly fall asleep.

As you continue to refine this method, you might notice that it can be shortened to approximately 2-3 minutes.

Learn to fall asleep by “progressive relaxation” method

Another great technique which was developed by the U.S. Navy Pre-Flight School to help pilots fall asleep quickly. The method is detailed in the book "Relax and Win: Championship Performance," and it's designed to clear the mind and relax the body within about 2 minutes, even in less-than-ideal conditions, like sitting upright or in noisy environments. Here's a summary of the steps involved:

Relax your facial muscles: Including the muscles inside your mouth. Tense each muscle of your face first to maximum for 5-10 seconds, and then relax them. This will allow you to learn how a relaxed face should “feel”. You can skip tensing the muscles prior to relaxing them after 2-3 weeks of daily practice.

This principle of maximally tensing each muscle and then completely relaxing it will apply to all subsequent points as well.

Drop your shoulders: Lower them as far down as they’ll go, followed by your upper and lower arm, one side at a time.

Breathe out and relax your chest.

Relax your legs: Starting from the thighs and working down to your feet.

Clear your mind for 10 seconds: Imagine a relaxing scene. If this doesn’t work, try saying the words “don’t think” over and over for about 10-15 seconds.

Hold this relaxed state: The goal is to clear your mind and maintain this state of physical relaxation.

The second method can be faster, but it is harder to develop. How about learning both? This only takes few weeks, will benefit you for the rest of your life, and also ticks the “Learn as much as you can” box?

Neuroplasticity and Learning New Skills: A seminal study by Draganski et al. (2004), published in "Nature," showed that learning new skills could lead to structural changes in the brain. The researchers found that gray matter volume increased in adults who learned to juggle, indicating that acquiring new skills stimulates brain plasticity.

Cognitive Reserve and Diverse Learning: The concept of cognitive reserve suggests that engaging in a variety of challenging and novel activities throughout life can contribute to brain health and resilience against cognitive decline. Stern (2012) in "Cognitive Neuroscience" discusses how a rich accumulation of life experiences and learning contributes to cognitive reserve, supporting the idea that diversifying one's learning experiences rather than solely focusing on improving existing skills can enhance brain health.

Learning New vs. Improving Skills: While repetitive practice of an already acquired skill is crucial for mastery and has its benefits, such as refining motor skills and improving efficiency, learning new skills exposes the brain to a wider range of stimuli and challenges. This notion is supported by research indicating that diversified learning experiences promote greater cognitive flexibility and creativity (Wiley and Jarosz, 2012, in "Psychological Science").

Challenges and Brain Stimulation: Engaging in challenging tasks that you're not already good at requires the brain to work harder to solve problems and learn new information, which can be more stimulating than practicing familiar tasks. This is supported by research on the "desirable difficulty" concept by Bjork (1994) in "Memory & Cognition," which suggests that learning conditions that are challenging (but not too difficult) enhance long-term retention and learning.

Hydration and Cognitive Performance" in the Journal of the American College of Nutrition: This study explores how dehydration affects cognitive function.

"Water, Hydration, and Health" in Nutrition Reviews: This comprehensive review discusses the role of water in human cognitive function.

"Effects of Dehydration and Rehydration on Cognitive Performance and Mood" in the Human Factors Journal: This research investigates the impact of hydration status on cognitive performance and mood, alertness and mental clarity.

Working Memory and Cognitive Load Theory: Research in these areas, such as by Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch's model of working memory. Cognitive load theory, developed by John Sweller, describes the capacity of working memory (triggered by immediate sensory input) is limited, affecting our ability to process new information while organising and storing it in long-term memory.

Multitasking and Task Switching: Earl Miller, a neuroscientist at MIT, has conducted research showing that the brain toggles between tasks rather than processing them simultaneously, which may relate to the idea of absorbing and indexing information not occurring at the same time.

Impact on Cognitive Performance: A study by Z. Li et al., published in "Nature Communications" in 2020, demonstrated that hunger significantly alters decision-making, making individuals more impatient and more likely to settle for immediate rewards over larger, delayed ones. This reflects a shift in cognitive strategy towards satisfying immediate needs.

Hunger and Learning: Research in educational settings has shown that students perform better on tests and are more able to concentrate when they are not hungry. A publication in "The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition" highlighted the positive impact of school breakfast programs on academic performance, suggesting that hunger detracts from the ability to focus and learn effectively.

Zone 2 workouts: Research has even found it can be more efficient than alternative training methods such as HIIT and high volume training for upping several benchmarks of athletic performance such as VO2 peak, time to exhaustion and power output.

Neurobiological Mechanisms: Aerobic exercises, including walking, running, swimming, and cycling, have been shown to stimulate neurogenesis (the creation of new neurons) in the brain, particularly in the hippocampus, a region associated with memory and learning. A seminal paper by Henriette van Praag et al., published in "Nature Reviews Neuroscience" (2002), discusses how physical activity induces neurogenesis and supports cognitive function.

Cognitive Engagement and Exercise: Repetitive exercises are characterized by lower cognitive demands, allowing the mind to enter a meditative-like state that may facilitate the processing and indexing of information. This is in contrast to complex physical activities that require continuous cognitive engagement for coordination, strategy, or skill application. The concept of a meditative state linked to repetitive motion and its cognitive benefits is discussed in "The Journal of Cognitive Enhancement" (2017) by Tracy and Wallace

The other forms of exercise are still excellent for overall physical health and performance. We are discussing here those that help to maximise cognitive performance, not physical fitness.

Exercise Duration and Cognitive Benefits: Research suggests that the cognitive benefits of exercise, such as improved attention and memory, often become noticeable after sessions of moderate intensity lasting around 10-15 minutes or more. This aligns with the observation that rhythmic exercise can aid in the indexing of information after the initial minutes of activity. A review in "British Journal of Sports Medicine" (2013) by Angevaren et al. supports the notion that aerobic physical activity improves cognitive function.

Cognitive Stimulation and Sleep Quality: A study published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine (2017) by Christensen et al. found that high engagement with electronic media around bedtime is associated with an increased likelihood of inadequate sleep quality and quantity among teenagers, suggesting that cognitive arousal from digital media use can impair sleep.

Screen Time and Sleep Delay: Research in the Pediatrics journal (2014) by Fobian et al. indicates that children and adolescents who spend more time on screens, especially in the evening, experience delays in sleep onset. This correlation is thought to extend to adults, with screen time interfering with the ability to fall asleep promptly.

Sleep Disruption: Harvard Medical School researchers have highlighted how exposure to screens, can disrupt the body's circadian rhythms, making it harder to fall asleep. Specifically, blue light suppresses the production of melatonin, a hormone that regulates sleep-wake cycles ("Blue light has a dark side", Harvard Health Publishing, May 2012).

Cognitive Arousal and Sleep Disruption: A study published in the "Journal of Applied Social Psychology" (2011) by Barber and Munz demonstrates how cognitive arousal from work-related electronic communication in the evening impairs individuals' ability to detach from work, leading to sleep disturbances. This illustrates how cognitive engagement, particularly with stress-inducing or thought-provoking content, can delay the relaxation necessary for sleep.

Sleep, Learning, and Memory Consolidation: A review by Stickgold (2005) in "Nature Reviews Neuroscience" emphasizes the role of sleep in memory consolidation. The research suggests that during sleep, the brain processes and organizes the day's experiences and information, a critical function for learning and memory. Interfering with this process by keeping the brain engaged with complex tasks or absorbing new information can hinder the transition into sleep.